I’ve wanted to make an application using the SAFE stack for a while and with our new indoor life it seems a good time to make a multiplayer games room.

This also presented a chance to try out using F# with SignalR for client-server communication and Akka.Net for a stateful game server.

Akka.Net

Akka.Net is a .Net port of the Akka actor framework. Actor frameworks provide useful abstractions to manage the concurrency, state and fault tolerance of applications.

Actors systems consist of actors that communicate asynchronously with immutable messages. Actors can be designed to effectively separate concerns and manage concurrency as each actor processes the messages it’s sent one message at a time.

F# is a great choice for writing Akka.Net applications due to some of it’s language features. The language’s default immutability, low ceremony record types and pattern matching over discriminated unions make defining and using messages very type-safe and expressive.

There are currently two libraries that interface with the framework, Akka.FSharp and Akkling, Akkling offers a slight advantage in type safety, although doesn’t work as nicely with some of the testing tools.

Actors are created by the framework with a props function and an actor computation expression. Defining an actor with Akkling requires specifying the Msg type it receives and the props the framework needs to create the actor.

type Msg =

| PrintInt of int

| PrintString of string

let createPrinterActorProps = props(fun (mailbox: Actor<Msg>) ->

let rec loop () =

actor {

let! msg = mailbox.Receive()

match msg with

| PrintInt i -> printfn "%i" i

| PrintString s -> printfn "%s" s

return! loop ()

}

loop ()

)The actor above receives a message that wraps either an int or a string and prints the value to the console.

The actor can be created by passing in a name to the spawn method along with the props and an ActorSystem to run in. spawn returns an IActorRef<Msg> that can be told a Msg with the custom operator <! that calls the actor’s Tell method.

// create the ActorSystem

let system = System.create "my-system" (Configuration.defaultConfig())

// tell the system to create an actor called "printer-actor"

let printerActor = spawn system "printer-actor" createPrinterActorProps

// tell the printer-actor a message it can handle

printerActor <! PrintInt 1The Akkling library allows for the type of the Tell call to be scoped to the Msg. This is an advantage over the framework’s standard Tell(object message), and from experience in previous Akka.Net code bases, could prevent a lot of dead-letter based bugs.

Games room

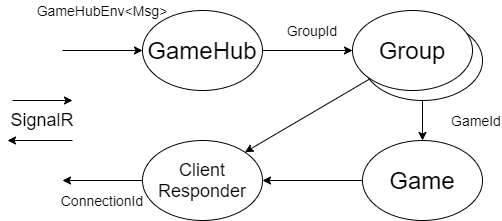

The games room consists of four different types of actors: GameHub, Group, Game and ClientResponder. The GameHub actor creates Group actors and is the interface for incoming messages from the clients. Each Group actor can send messages back to the clients via the ClientResponder actor or to the groups active Game actor.

Each message is wrapped in an envelope that contains identifiers to direct it to the Group/Game actor and for the ClientResponder actor send to any resultant messages back to the client.

The GameHub and ClientResponder actors provide useful in/out points for testing the system. Messages from the client hub can be simulated by sending them to the GameHub actor and the ClientResponder can be replaced with an actor that passes messages to an Akka.Net TestProbe where the ExpectMsg method can be used.

SignalR

SignalR is a solution for painless client-server communication over websockets. An advantage for using F# is that it allows the same DTOs to be used in the client and server code for the transfer of complex objects.

This is the first time i’ve used the library, the setup on the server-side is the same as C# and is well documented.

SignalR works well with F# objects as long as camelCase is used for property names and the DTOs are simple records that use the CLIMutable attribute on the server-side.

I chose to use the non-native-F# version of types where possible (array over list being an example) and didn’t try to use any discriminated unions.

Sending a int array from the client required serialising it to a string, as the fable representation of the array was a simple object, rather than a javascript array.

The client-side setup required a bit of work to produce the fable bindings. The ts2fable tool produced a starting point for the typings that were easily tweaked.

I didn’t find a way to make the send and response totally type-safe, but the responses from the server are easily cast to the record types that are shared across the client and server projects. The responses need to be converted into the Msg type of the application and can easily be dispatched into the update loop with an elmish subscription.

SAFE stack

The SAFE stack dotnet template is a great tool for the initial setup, I shudder to think about some of the mistakes it would be possible to make when setting these technologies up.

I initially deployed the project to Azure App Service, but my wallet got the best of me and convinced me to use a digital ocean droplet. The FAKE script made it easy to build and store a docker container using Azure Devops and dockerhub.

Overall I’m a paket convert, although it took me a bit longer to figure out how to add a package than i’d like to admit. It might be a good place to expand on the documentation and hopefully the planned SAFE stack recipes will clear up some confusion in the future.

Conclusion

Overall the experience was a very pleasant one. The functional style of writing app state is a great way to express the intent and limit the possible app states with the compiler.

Being able to use the same language in the client and server code is very cool. I only encountered one null-based error in the front end code, which is counter to most of my javascript programming experience. Being able to use match expressions on the client side code really does seem like a “game changer”.

As other people have suggested, the code took a bit longer to write than I would expect a similar app to be written in C#/javascript, but this was partly due to figuring out some of the quirks of using the technology together.

There’s a saying, ”Weeks of coding can save you hours of planning” which applied to this app and I plan to spend a bit longer on the design of the next one. Halfway into the implementing the front-end I figured out a better design that required some fairly radical refactoring. The F# type system really came to the rescue, and i’m fairly sure I would have binned the first attempt has I been using another language.

The site is up and running at gamesroom.xyz. I’ve open sourced the code in the hope it’ll help others and/or people will be able to constructively critique the elmish app layout. If you have any feedback i’d greatly appreciate it in the form of an issue on the repo :)